By Cynthia Haven

The 20th century world of philosophy did not, as a rule, create superstars.

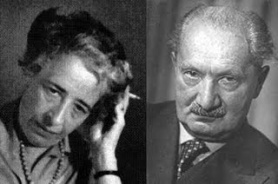

Hannah Arendt was an exception – almost from the time she coined the phrase that has become a cliché, “banality of evil,” to describe the 1961 trial of Nazi Adolf Eichmann in a series of articles for The New Yorker. She acquired a cult status that her mentors, philosophers Karl Jaspers and Martin Heidegger, could hardly imagine.

Thirty-five years after her death, the German-Jewish political theorist, author of Eichmann in Jerusalem, Origins of Totalitarianism, The Human Condition and Life of the Mind, among other works, is an international industry, with new letters, commentaries and biographies published every year. But perhaps her message has been obscured by celebrity.

A scholarly conference at Stanford attempted to redress the imbalance in its own way with a recent two-day workshop, “Hannah Arendt and the Humanities: On the Relevance of Her Work Beyond the Realm of Politics,” sponsored by the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies. Scholars from around the world discussed the life and thought of one of the most seminal and influential political philosophers of the last century.

A friend remembers

In a surprise appearance, Stanford University President Emeritus Gerhard Casper spoke of his friendship with Arendt, from their meeting in 1961 until her death in 1975.

“Why Arendt? Why Arendt now?” asked Professor Amir Eshel, director of the Forum on Contemporary Europe. He said that in the humanities, her “insights about the link between the past and the future” can “address the predicaments of our time, specifically such manmade disasters as genocide and mass expulsion.”

Arendt fled Germany when Hitler rose to power in 1933, immigrating in 1941 to the United States, where she taught at a number of universities. Her works, particularly The Origins of Totalitarianism, a study of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes, spurred a wide-ranging debate on the nature and history of totalitarianism. Her books analyzed freedom, power, evil, political action – and, always, thought.

Stanford professor Robert Harrison, chair of the Department of French and Italian, made the conference’s most spirited address in a talk on “passionate thinking.” He considered Arendt’s notion of friendship and thought as rooted in solitude and the ability to commune with oneself – that “plurality begins with the individual.”

The “overwhelming question” in the humanities, he said, is “How do we negotiate the necessity of solitude as a precondition for thought?”

“What do we do to foster the regeneration of thinking? Nothing. At least not institutionally,” he said. “Not only in the university, but in society at large, everything conspires to invade the solitude of thought. It has as much to do with technology as it does with ideology. There is a not a place we go where we are not connected to the collective.

“Every place of silence is invaded by noise. Everywhere we see the ravages of this on our thinking. The ability for sustained, coherent, consistent thought is becoming rare” in the “thoughtlessness of the age.”

Harrison decried the public fascination with Arendt’s youthful affair with Heidegger, a Nazi sympathizer; the publication of Arendt’s personal letters; and her biographers’ invasive use of private material – although at least one biographer, Thomas Wild of Berlin, author of Hannah Arendt, attended the workshop.

Casper said that he had to be “cajoled into coming” as Arendt was “a very private person.”

“She would not have approved of videos, being taped at all times and put out on the web,” he said, indicating the camera that was filming the event.

He noted that “she liked to gossip – very much so.” However, he said, “What she would have been appalled by is the industry. Cottage industry? This is hardly a cottage industry anymore.”

Guarded her solitude

Casper reinforced the notion of Arendt as a guardian of her own solitude: attending conferences infrequently and “always thinking … always fiercely independent,” protecting her “private time, time for study, time in her apartment on Riverside Drive.”

“She was forceful, opinionated, never had any doubts about her views,” he said. “In certain circumstances she was willing to listen carefully and be convinced she was wrong. Those were rare.”

Casper said he considered her best book to be Eichmann in Jerusalem, a book that concluded, famously, with a direct address to Eichmann:

Just as you supported and carried out a policy of not wanting to share the earth with the Jewish people and the people of a number of other nations – as though you and your superiors had any right to determine who should and who should not inhabit the world – we find that no one, that is, no member of the human race, can be expected to want to share the earth with you. This is the reason, and the only reason, you must hang.

“She was incredibly good when she observed, when she told what she saw,” Casper said. “She was incredibly suggestive and artistic – she was not definitive, not scientific,” he said. “That’s why she’s not popular among philosophers, nor among political scientists. She was putting forward a kind of truth, not definitive, about the human condition. That was her great strength.”

Arendt is more than another talking head; Eshel said that she forms a formidable counterpoint German philosopher Walter Benjamin’s view of the past “as one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage at the feet of the angel of history.”

Arendt instead “wants us to acknowledge our ability to set off, to begin, to insert ourselves with word and deed into the world. Arendt seemed to have sensed that if we do not do so there may be indeed no future for us to share.”

In: http://news.stanford.edu/pr/2010/pr-hannah-arendt-conference-052510.html